By: Chris J. Rufer

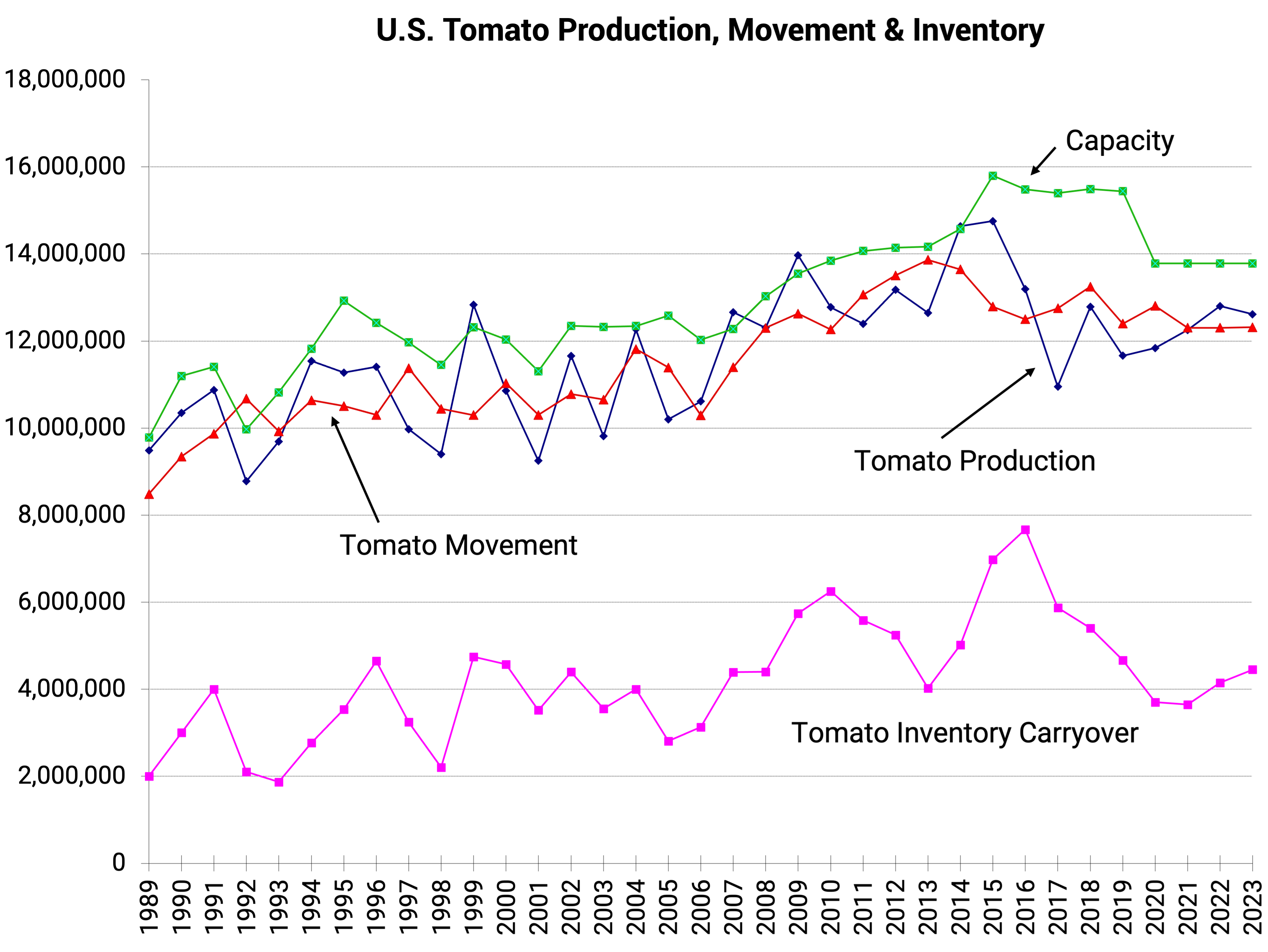

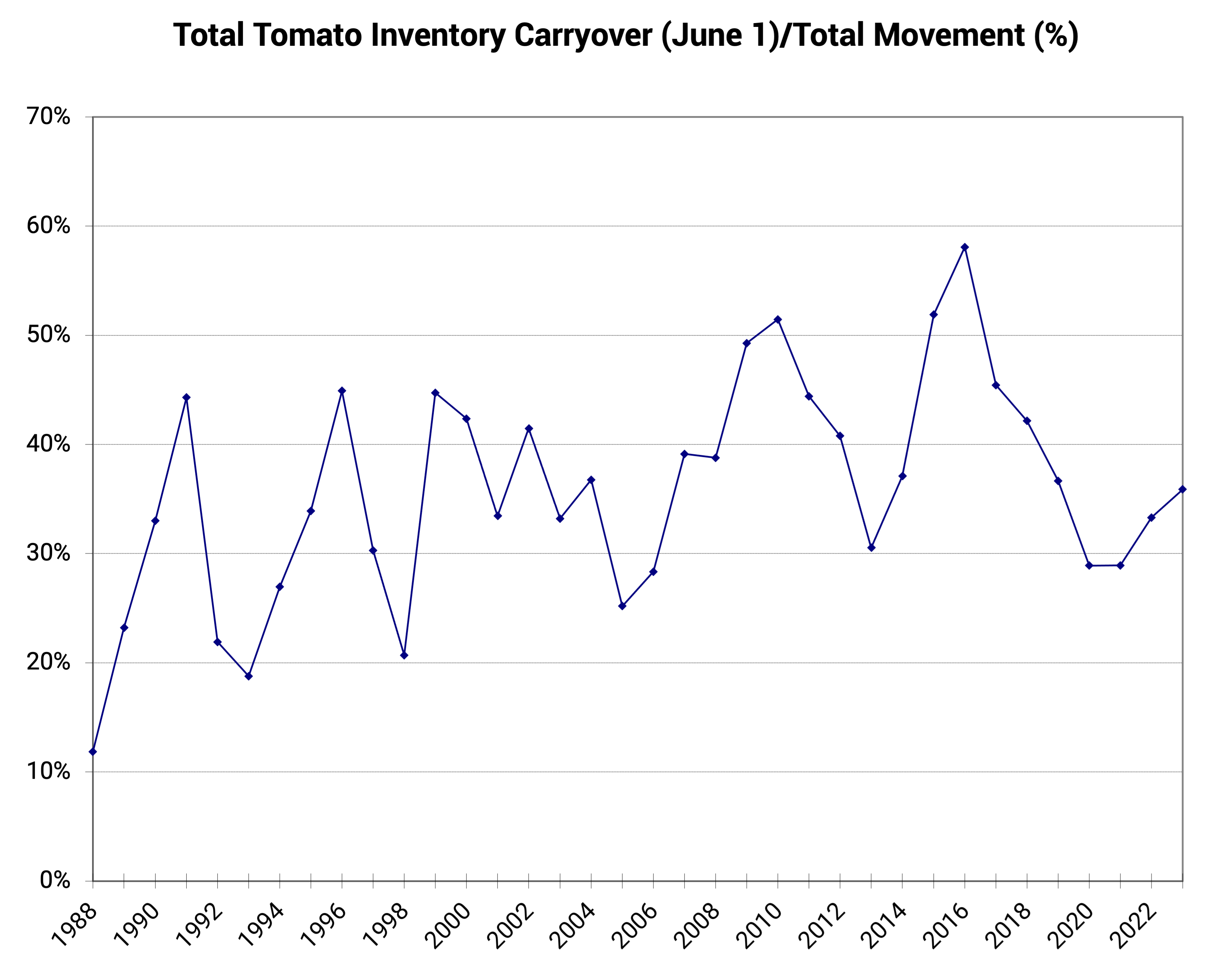

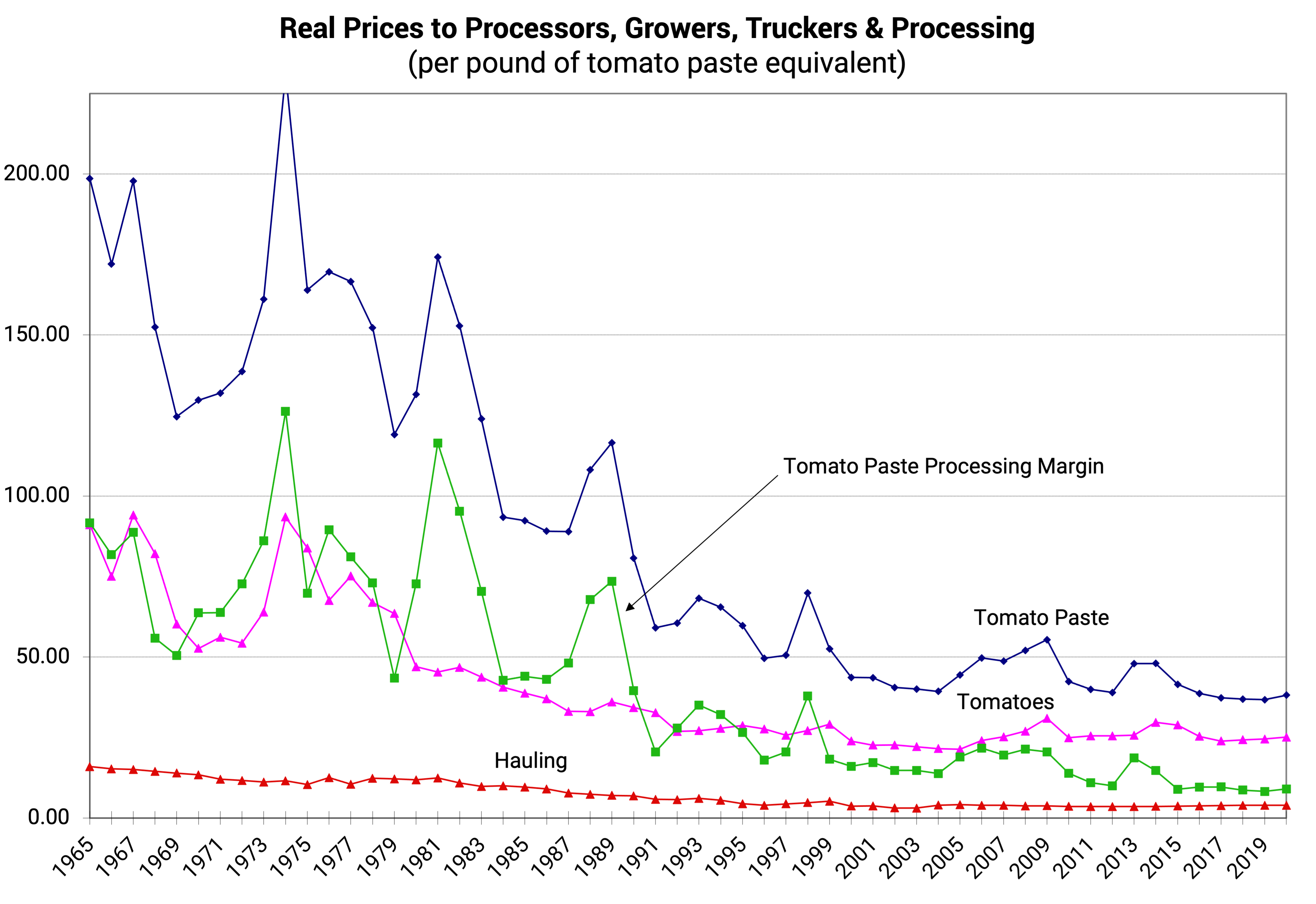

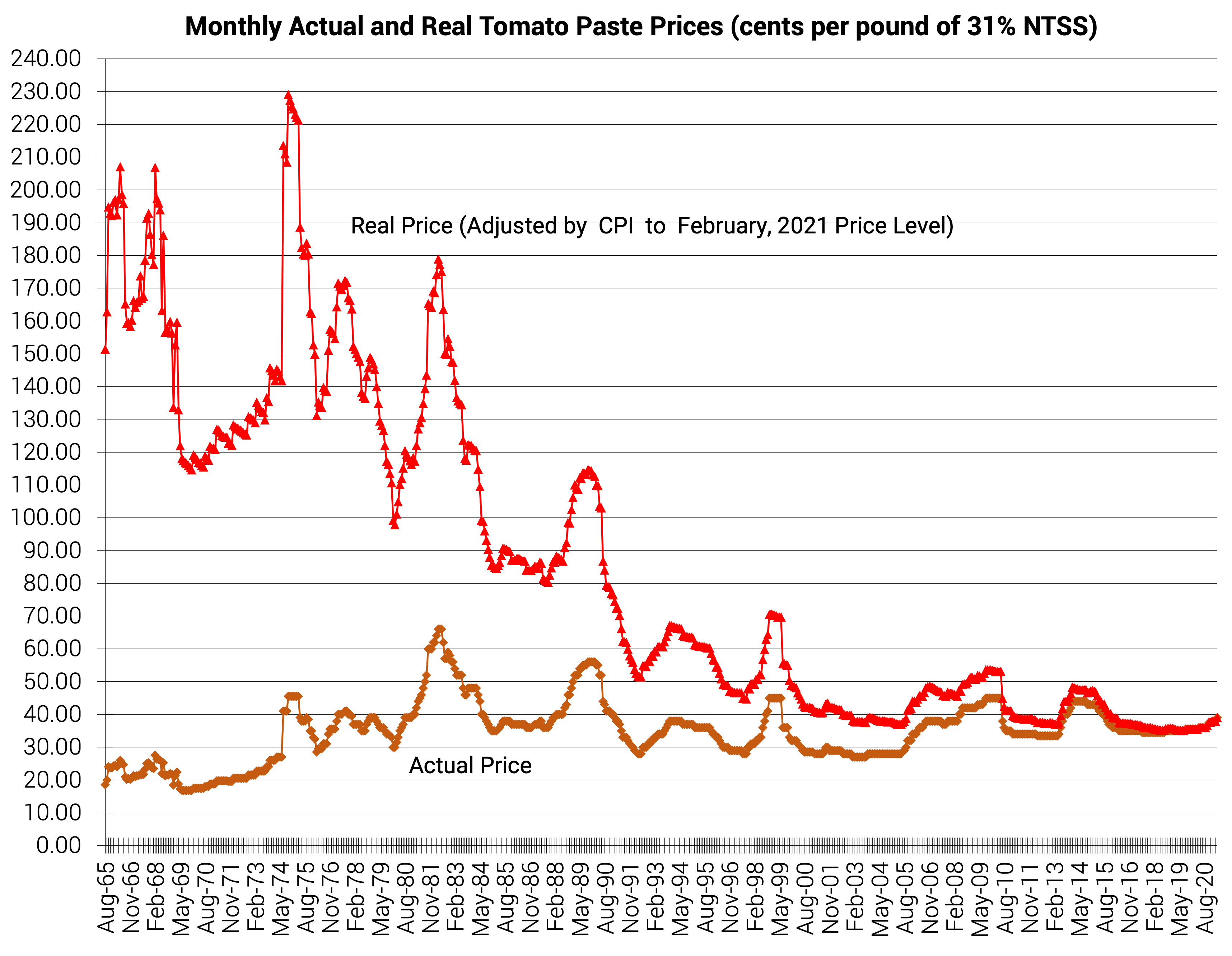

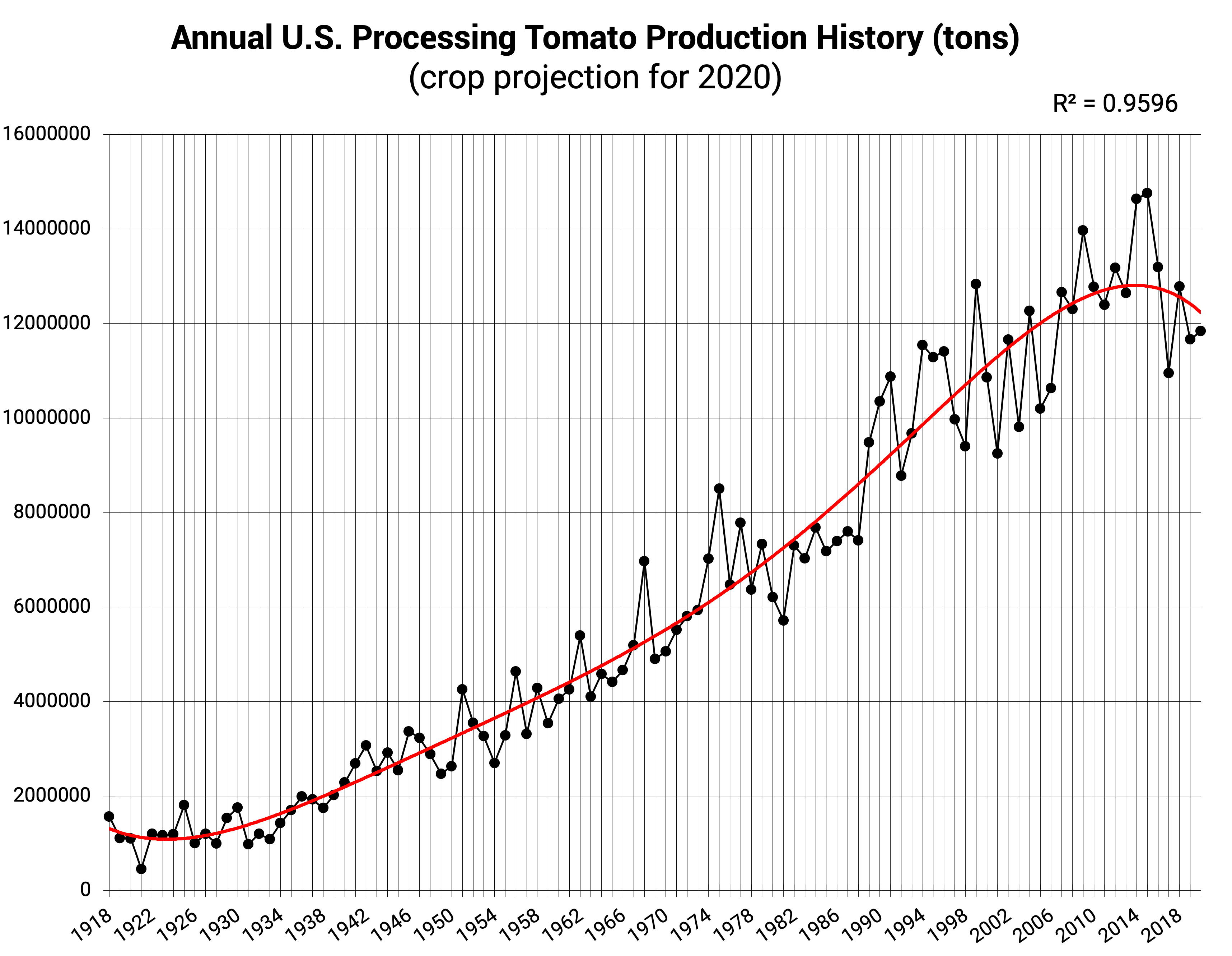

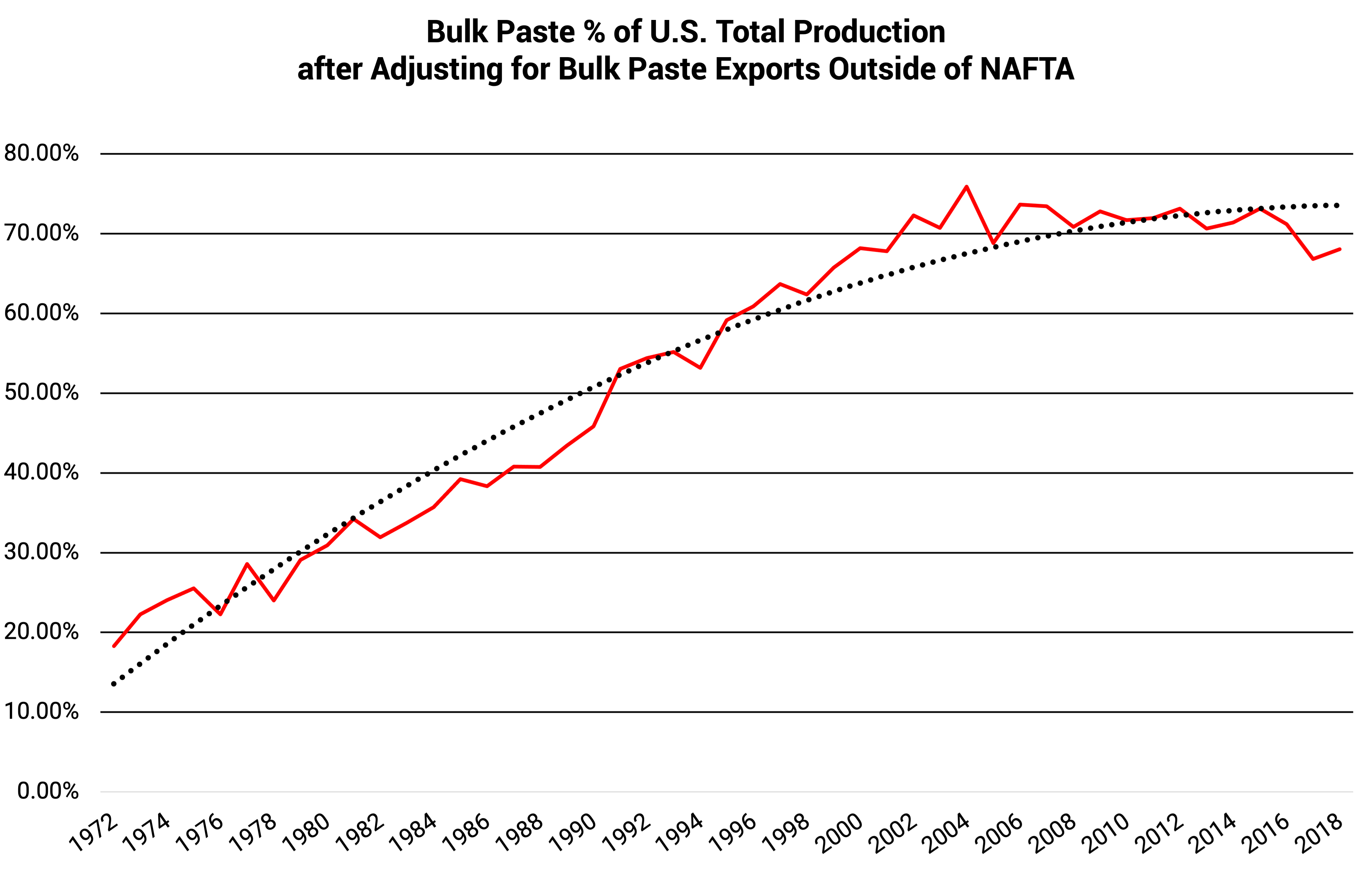

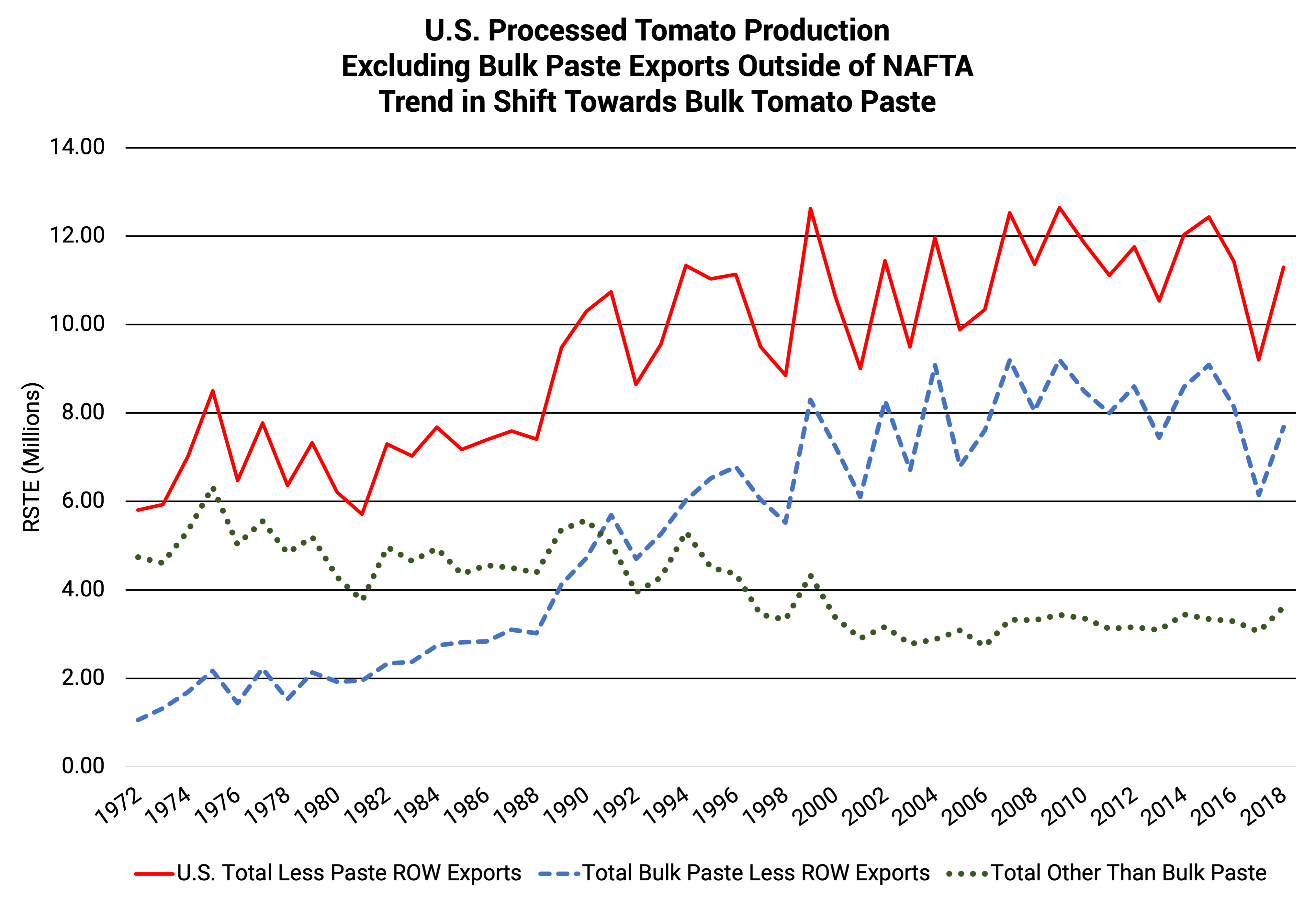

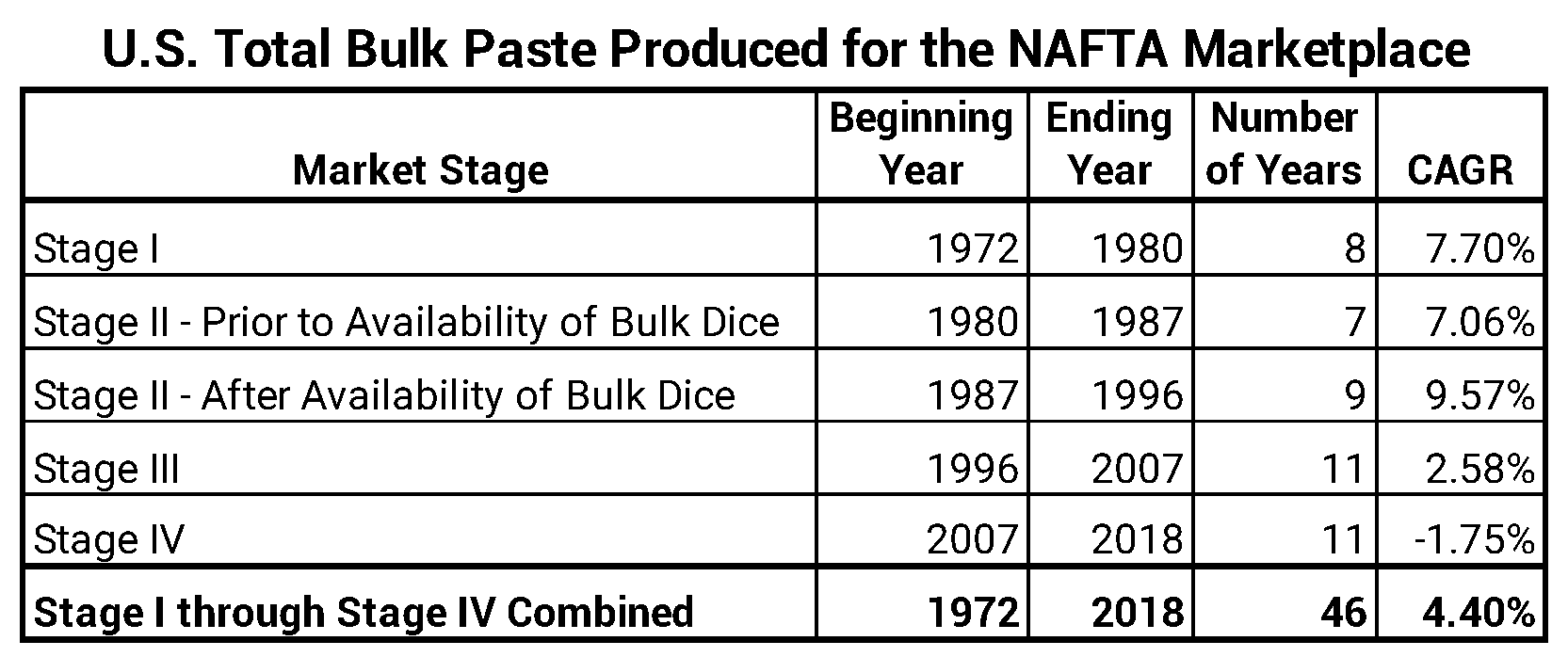

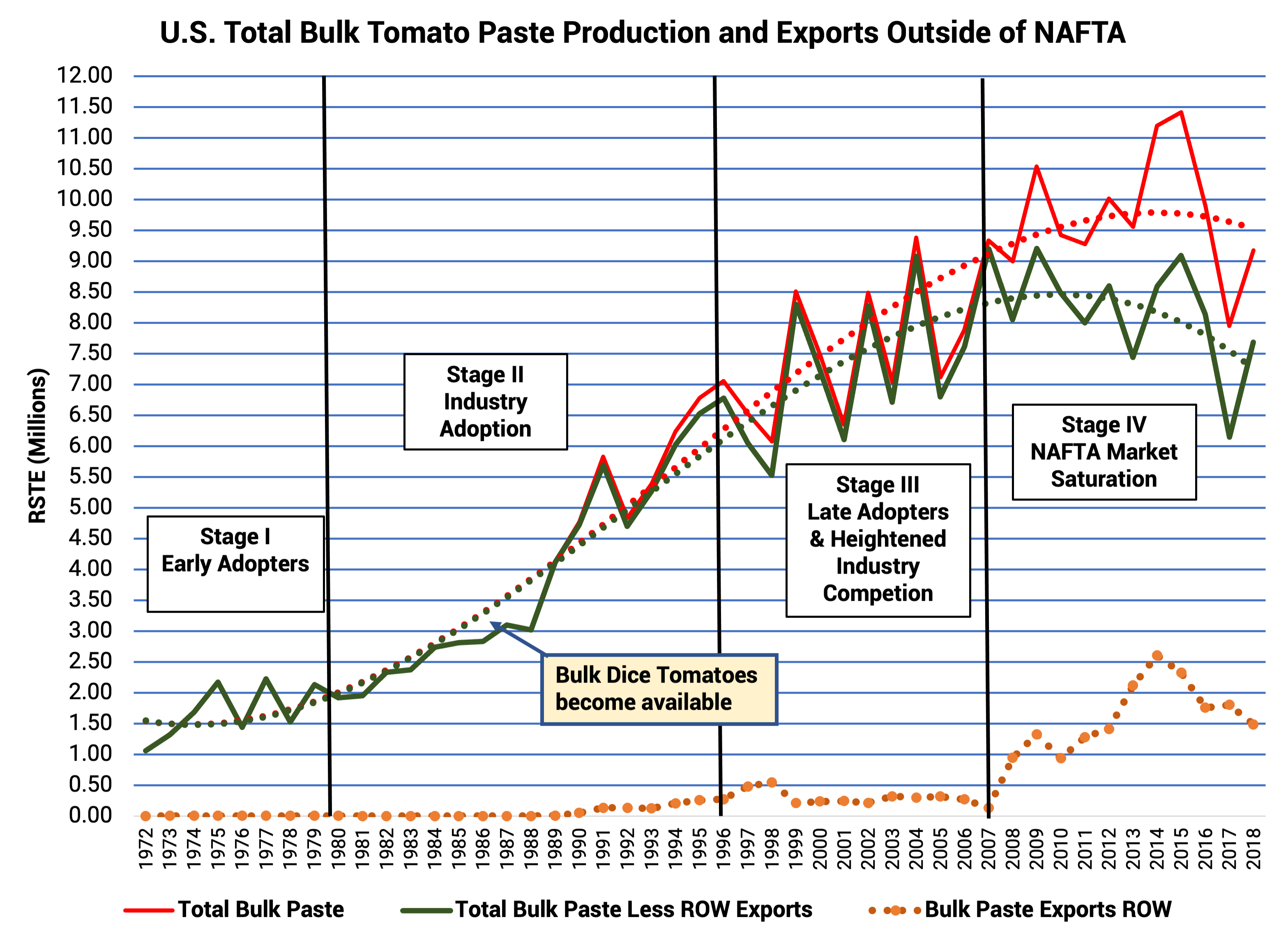

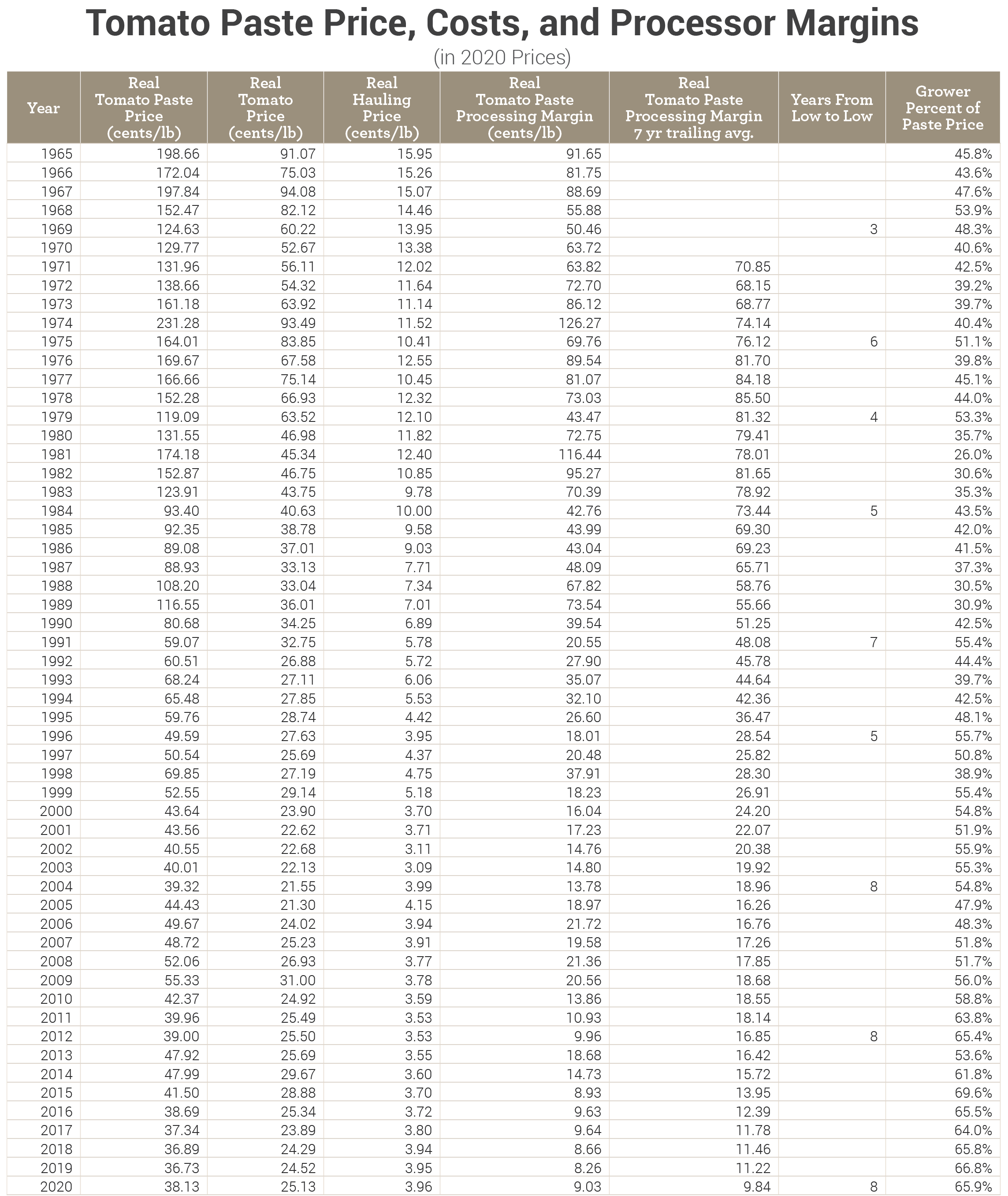

Our California processing tomato industry has a history of meaningful ups and downs in production volumes, prices and profitability–as almost all industries do. (See Exhibits A, B, C & D)

The Story

It’s a story of producers/suppliers languishing at prices just over variable costs for four or five years. Factories are closed and torched, and companies disappearing from bankruptcies or choice are the features of the languishing as we all fight for extra sales, which are not there in the marketplace as a whole.

It’s also a story of exuberance. For the following two years, profits are high, new factories are built and older factories expand wherever they can. The attitude takes hold that prices can only go up (e.g., the stock market and houses, right?). Plus, the demand for our processed tomato products seems to be expanding at a high rate.

That is the history of what I have seen and ridden for almost forty years. I have tried to study the markets and industry structure for this entire period with limited success at getting it right. The “invisible hand” of the markets is truly, reasonably invisible–at least to me.

My Big Mistake

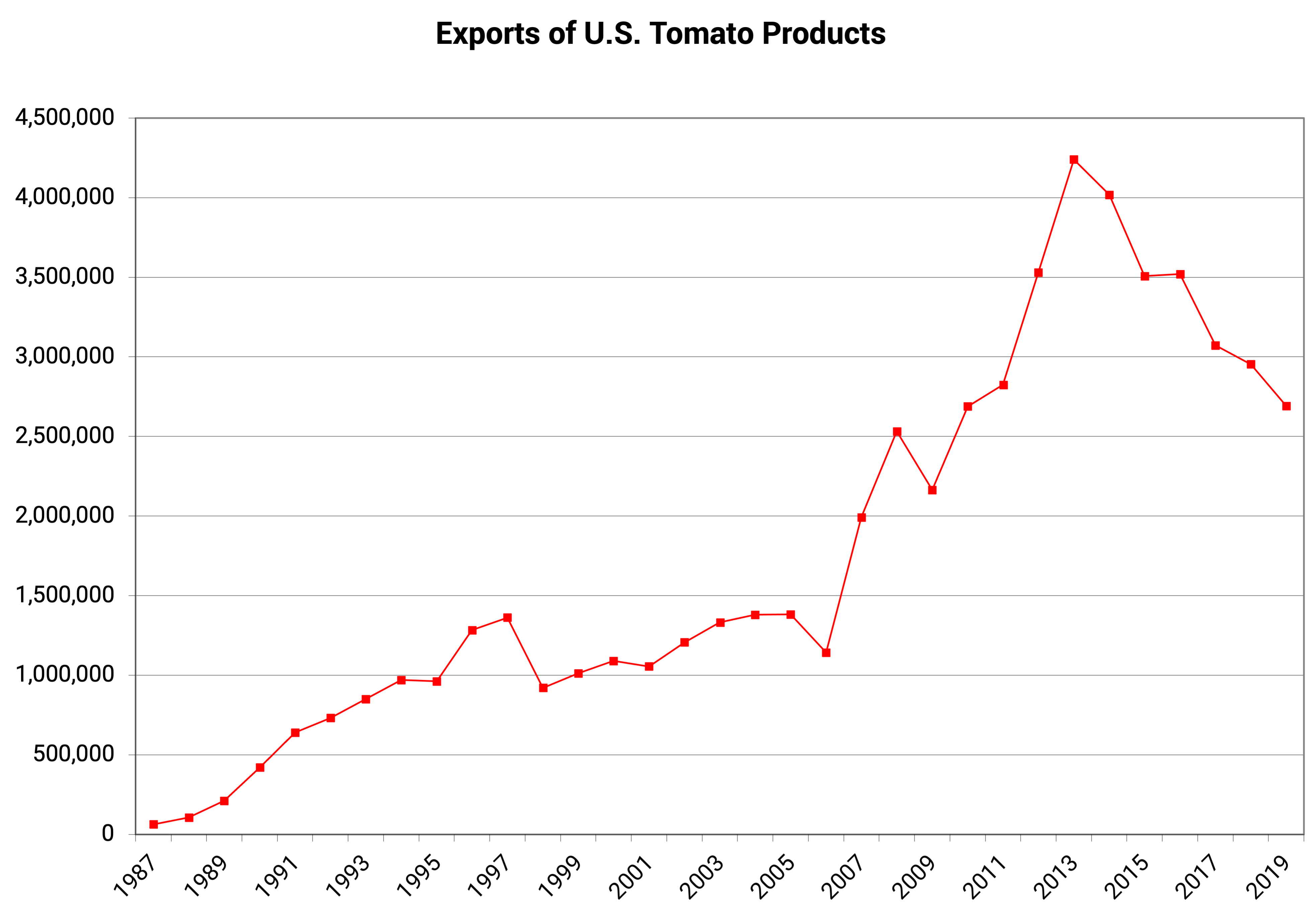

I do remember well the last big mistake I made, one of many, of course. We (The Morning Star Packing Company) made a significant expansion in 2015, which left us with high inventories and excess capacity. It wasn’t just us, but we were a large part of it. But, this mistake was only in retrospect. As one can easily see in Exhibit E, market volumes were increasing pretty well from exports leading up to 2014 and 2015. A few factors lead up to this growth.

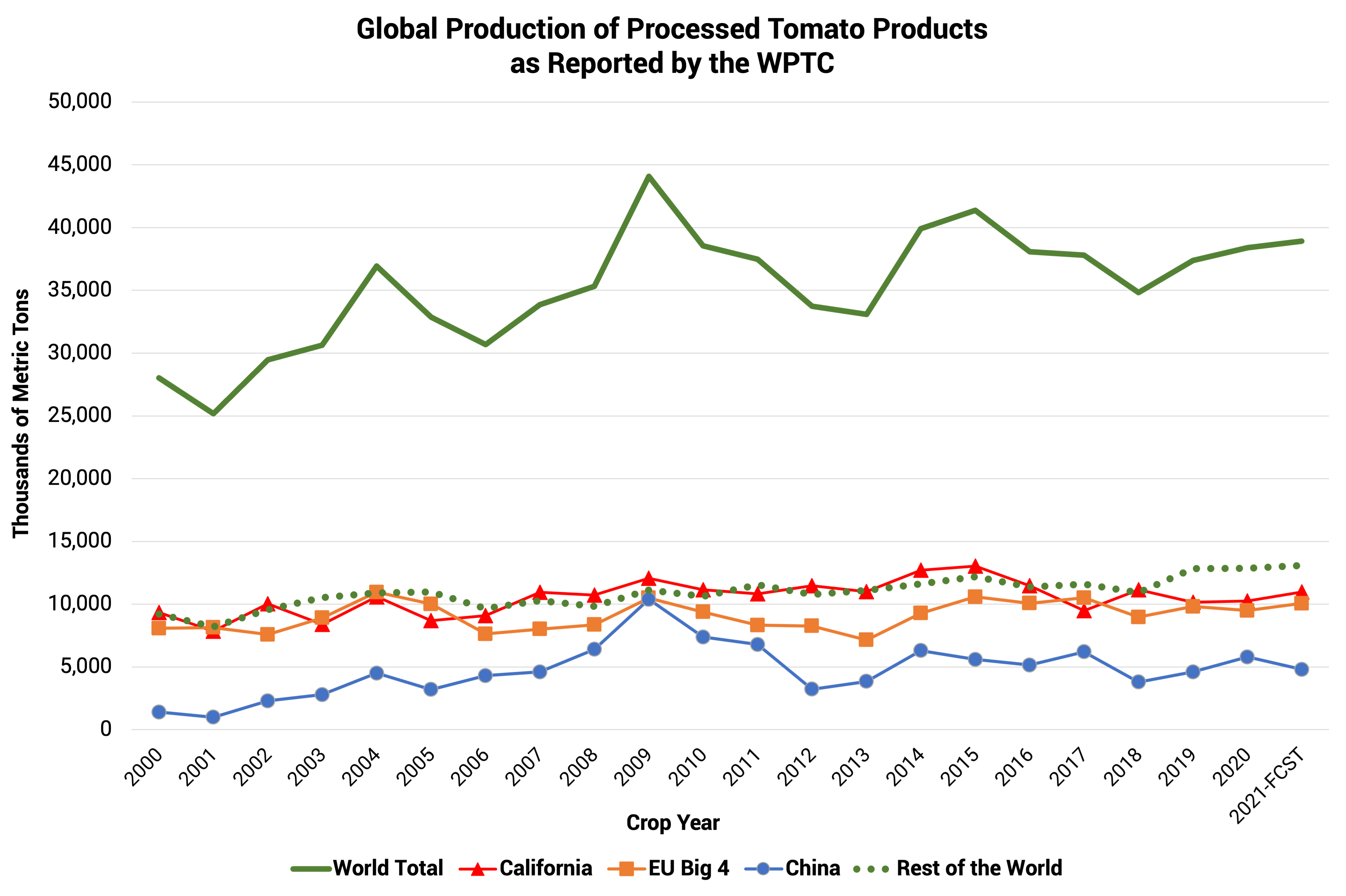

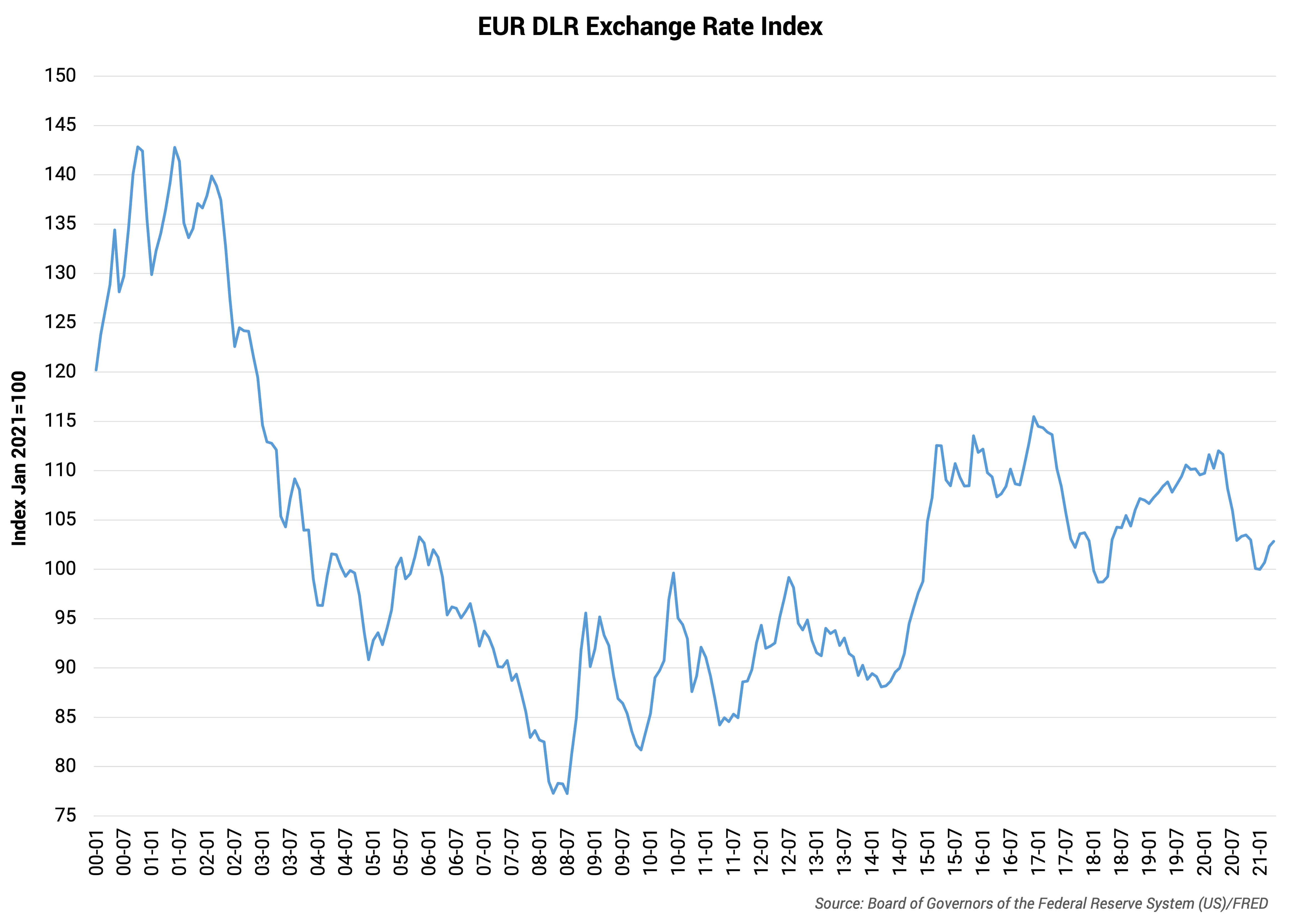

In the prior five (5) years, production in the European area decreased, China finally realized its losses and consolidated considerably and the Euro/Dollar relationship changed in favor of U.S. exporting (Exhibit H & Exhibit I). But then things changed again. The European area and China stabilized production, the Euro dropped from the 135 (dollars per Euro) range to under 110, plus smaller world producers (e.g., Ukraine, Russia and Tunisia) increased production.

California tomato paste exports have been in free fall ever since.

In 2014 when I decided to expand, I reasoned that if the exports did not rise as fast or as they had been up to that point, or if they even dropped, we could use our increased capacity to shorten the length of our season. By doing this, we could eliminate some late-season premiums to pay for the investment partially.

In one of our side businesses, I have a long-term partner; he commented to me some years ago to the effect of, “You only operate your factories so you can continue to build more. You’re really a construction company.” Some truth to this. So, while being on the fence economically, relative to deciding whether to expand in 2014-15 or not, I tipped to an exciting construction project and expanded production.

Industry Correction

Since 2015, our industry has fought very high inventories and over-capacity, as shown in the various Exhibits previously referenced. However, after the languishing of 2016 through 2020, the 2020-2021 years saw four factories close and two companies exit the business. One thing I have been pretty accurate at is predicting which factories will close next by tracking cost structures by factory and year.

All four of these shuttered factories (Hunts in Helm, both Olam (former SK Foods) factories in Lemoore and Williams plus Mizkan (Ragu) in Stockton), had structural cost problems. The SK Foods Lemoore factory problems were so bad that they significantly contributed to SK’s false inventory reporting, buyer kickbacks, collusion and finally bankruptcy and jail times.

A Golden Opportunity

With these closures, the industry has found new footing with a good balance of market volume requirements, inventory and capacity. Without those closures, we would still be languishing in red ink.

Am I going to repeat my mistakes? Is our industry going to repeat our mistakes?

The Market for California Ingredient Tomato Paste

As can be seen in Exhibit F, the market size for our processed tomato products has flattened. There is solid, stable demand domestically, and at some point in time, exports will also level off at some lower level–but where? In Exhibits J-1 and J-2 and Exhibits K-1 and K-2, one can see just how flat our market demand is and especially in lieu of the impact of the export volatility. We are clearly dependent on export potential for any volume growth and at more risk for volume losses from decreased exports. These are markets very reliant on prices, but just the Euro/Dollar improving in our favor will not be enough to correct our competitiveness relative to other world producers.

At this point, our foreign competitors in Spain, Chile and Canada, have seen their farmers making good improvements in their crop yields versus California farmers. As you can see at the bottom of Exhibit G, the processing sector has made considerably more progress in lowering costs and prices than the farming sector. The California processing tomato industry is hanging in there competitively, but expectations for exports appear highly questionable. Increases in paste pricing of over 25% this year could only influence exports to decrease; however, foreign prices have also increased, and the Euro has dropped against the dollar. What is going to be the result of this balance? I see flat to lower exports.

I once experienced being in an industry where its markets were decreasing in volumes, and it was a terrible situation–processing peaches (down from 1.5 million tons to now 250,000 tons). From tens of fruit processors but only a few decades ago, we have two remaining peach processors–Del Monte and PCP–a public, branded product company and a grower cooperative. Amazingly, their grower yields have not changed in at least forty (40) years. Grower innovation is vital to product volumes! Our California olive industry has only two remaining participants.

When an industry is experiencing an increase in market demand, prices are generally higher than cost structures and cycles from bottom to bottom are shorter. When market demand is flat, or especially when it is decreasing, these cycles are longer, and a depressed market situation for producers seems never to end (with prices barely above variable costs).

The California processing tomato industry is now in this same flat to decreasing market demand, shown in Exhibit G, in the column showing processing margins and titled “Years from Low to Low.” Now is not the time for expanding capacity–it is a death sentence for those who do. But, we always seem to be suckered into expansion in the face of higher prices. How suckered?

Nuances in the Current Market Situation

It is easy to see these trends in the Exhibits; however, some nuances drive these trends and make the ups and down accentuated–which is what is going on today and which everyone should carefully consider.

To review the ups and downs drivers, let’s begin the scenario with an industry situation of short inventories and balanced capacities (like we are at now). Here, prices go up to stop the factory closures and arrest the industry’s financial bleeding. This bleeding needs to stop because processing tomatoes are a good product with solid demand. Processed tomatoes are key ingredients used throughout the world, especially in American food meals, such as ketchup for burgers and fries, pasta sauce for pasta meals, pizza sauce for pizzas, and a plethora of other foods from salsa, BBQ sauce, meat sauces, tomato juice, frozen meals, etc. Furthermore, the cost of the tomato paste and diced tomatoes are a relatively small cost component in these core American meals.

While buyers of our products don’t admit it during our periods of languishing prices, excess inventories, and hungry processors, reliable supply is far more important to them than price, which explains why, when there is a hint of a supply shortage like now, prices spike. Even in the face of the basic supply/demand situation presenting as somewhat tight–but not “short.”

During this period of low inventories and price hikes, the key nuance is that buyers over-book their requirements. When buyers perceive the potential for a short supply, they try to cover themselves by asking for more product than they truly require. When calls to their regular supplier(s) for more product are rejected or are “put on a waiting list,” or they hear, “we’ll have to wait and see how the pack goes,” such that their suppliers appear to be reasonably full, they start calling all other suppliers.

Assuming one buyer, whose annual usage is five (5) million pounds, has two (2) regular suppliers and has asked each of them for an additional million pounds of tomato paste to no concrete avail. They then call each of the three (3) other remaining suppliers and ask each of them for a million pounds. “The industry” now sees a total “increase in demand” of five (5) million pounds–which is all phantom demand.

Take this further with an estimated two hundred (200) buyers with meaningful volume and well over two (2) billion pounds of total requirements. The above over-booking scenario could result in each supplier perceiving an increase in demand of up to 100%–all of a phantom nature. Not every buyer over-books nor over-books by 20%, but the perception is that demand has increased.

There is a saying that “perception is reality,” but the reality is that only accurate perception is reality. Correctly, people do act on perceptions, but acting on inaccurate perceptions leads to mistakes.

This activity also increases prices even more than the supply and demand balance would dictate to the degree this activity occurs.\

At this point in the industry cycle, the result of this scenario is that producers are encouraged by phantom demand and high prices to expand. If one studies the timeline of new factory openings or significant expansions, you will notice that they are lumped together a year to two after this scenario appears.

Of course, when this expansion occurs, it over-corrects and we over-produce–in spades (Exhibits A, B & F), and prices decrease. Then, the California processing industry and every company within it experience three to five years of depression (five or six years this last cycle). This time around, if expansion repeats, I would expect this scenario to be the most prolonged depression we have ever seen. (1) all remaining producers are well-positioned, relatively, to weather the next storm, so capacity will remain for a long time, and (2) we won’t have market growth to get us out of the imbalance of high inventories and excess capacity.

These past few months have seen ingredient prices go up over twenty-five percent (25%). Buyers and producers typically say they desire predictability in availability and pricing. If there is integrity in these statements, two things must occur, as follows:

(1) Buyers. Buyers need to stop over-booking and go to their current suppliers with realistic requirements to eliminate the phantom demand and moderate price increases. We all know marketing folks are optimistic, as that is their character, but they need to be taken to task. Please remember that the final demand is from the physical consumer, and I can’t see them eating any more than previously. Can you? What one salesperson/company gains in sales will be taken from another company with no net increase in demand for any bulk tomato paste or diced tomatoes.

While current and short-term inventories are low in the industry cycle, and some suppliers are playing the scare game in talk and not quoting pricing, the industry evidence is such that the low inventories are at a “normal” low for the cycle. Even if the crop is slightly below current expectations, we should have enough to get by. Further, buyers’ over-booking will not increase supply from the 2021 crop–that is a done deal as of now, only subject to forthcoming weather and unknowns (like COVID a year ago).

Again, buyers need to stop over-booking.

(2) Producers. The last time around, when we saw high phantom demand and higher prices, we expanded capacity and production. We then experienced ingredient product prices go down sharply by about twenty-five percent (25%). To add insult to injury, we paid a high price for tomatoes ($83/ton in 2014 and $80 in 2015)–a nasty double whammy. Therefore, prospectively, any additional production capacity put online at this time for additional ingredient tomato paste or diced tomato production will cause a fast and significant build-up in inventories and another quick industry depression. Producers should look to increase hours of production in 2022 to make up for moderately short inventories coming out of the 2021 season–not adding additional capacity.

Although, of the current seventeen (17) tomato processing factories operating today (not just for tomato paste), there are still, in my book, four (4) factories that could be closed to improve industry competitiveness. I would do this if I owned the entire industry, but I don’t. These factory owners are fine continuing to operate them and have no known financial problems. There are three (3) factories that could easily and very cost-efficiently expand to cover their production volumes.

Today, over 75% of California’s tomatoes are processed into bulk tomato paste, making it, by far, the largest California processing tomato product. Furthermore, we are currently down to only five (5) tomato paste suppliers–all of whom appear reasonably well-financed and productive. There are no noticeably weak producers anymore.

Summary

In summary, in my opinion, the California processing tomato industry is in a perfect balance of market demand and production capacity. We’ve seldom, if ever, seen this situation before and had the opportunity to have moderate but sustained viability for an extended period of time. We will realize this if we prevent over-booking, the appearance of phantom demand. A higher than fundamental supply/demand balance would drive prices and additional capacity brought online.

As needed, current capacity can operate for an extra 156 hours in 2022 (almost exactly one (1) week) to produce an extra one (1) million tons, which is very doable. Even doing that for only two (2) years will build up inventories to excess levels again.

But personally, my inclination is to design and construct, and we have the room to do that. But sitting back to think, I’m going to find a use for that desire and capability elsewhere, based on these lessons and current facts of our industry situation. I think Warren Buffet’s “genius” is not so much in his given intellectual genius, but in his discipline–when things get good, hold on, build your cash and wait for other opportunities–they’ll come and sometimes out of nowhere.

We always seem to have the ability to shoot ourselves in the foot again. Do we want to? Will we do it again?

Respectfully yours,

Chris J. Rufer, The Morning Star Company

Morning Star Newsletter now distributed electronically

As a reminder, Morning Star is now distributing our newsletters electronically using an email distribution vendor called Mailchimp. Your e-version will now include informative Morning Star videos and highlights. Depending on your company's firewall, these emails may initially be directed to you spam folder.